Going Deep: Lessons from Six Global Ocean Conferences

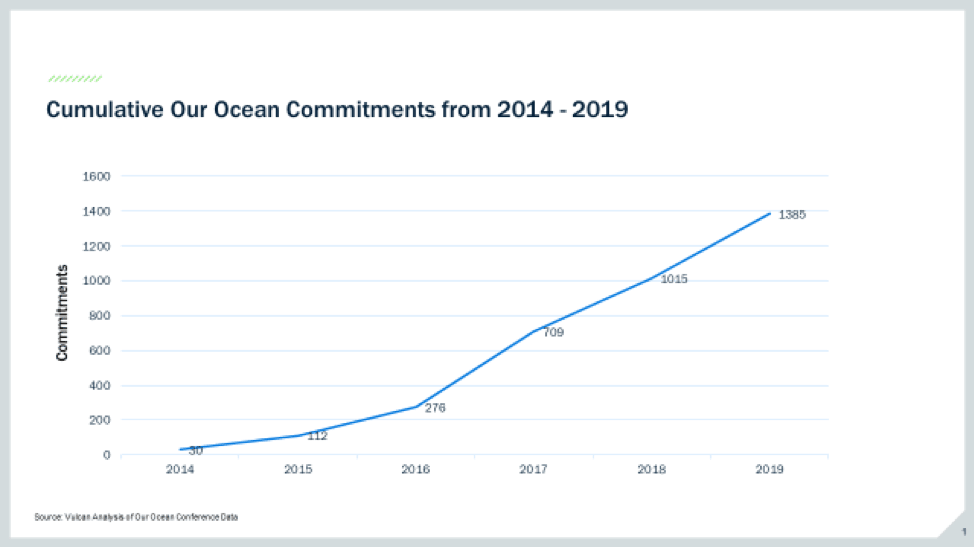

Ocean leaders just concluded the sixth Our Ocean Conference in Oslo. Since 2014, participants have announced 1,385 commitments to improve the health, resiliency, and security of the world’s seas. These are the lessons learned and what needs to happen next.

Global ocean leaders met in Oslo last month for the sixth installment of the Our Ocean Conference where participants announced 370 commitments to improve the health, resiliency, and security of the world’s seas. Making commitments is a centerpiece of this annual event, and since 2014, governments, intergovernmental organizations, the private sector, foundations, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have made 1,385 of them. Over the last few months, we analyzed the commitments and this is what we found.1

Race to the top

Undeniably, the Our Ocean Conference has generated a race to the top mentality among actors across the public, private, and not-for-profit communities. For example, during the first Our Ocean Conference, Palau’s president Thomas Remengesau Jr. proposed a new no-take National Marine Sanctuary covering 80 percent of the country’s exclusive economic zone. This was a dramatic and bold statement for an island nation dependent on foreign revenue fishing in its waters. Palau’s move, in part, triggered other countries to follow suit, and since 2014, 55 countries have used the Our Ocean Conference platform to announce that they too will preserve and protect large parts of their territorial waters, including Chile, Seychelles, the United States, and the United Kingdom.

That same year, the government of Norway made a $1 million commitment to study measures to combat marine plastic waste and microplastics. Since then, 100 other actors have made similar commitments to combat plastic pollution at Our Ocean conferences.

Without a doubt, the Our Ocean Conference has been a catalyst for action.

Show me the money

In 2019, conference participants self-reported a total of $63.7 billion in commitments, up from $1.8 billion committed in 2014. This is a tremendous influx of resources into the generally cash-strapped marine health community.

However, the lion’s share of this total—over $50 billion—came from two commitments made by the Norwegian bank DNB ASA, for financing renewable energy projects and infrastructure, and the Asian Development Bank for its Action Plan for Healthy Oceans and Sustainable Blue Economies. Removing those two commitments brings the total commitment amount for 2019 to $9.7 billion, which is consistent with the value of commitments in recent years.

Despite the plethora of commitments and their significant financial value, oceans remain under-prioritized and underfunded. For example, a recent study polling 3,500 politicians, bureaucrats, nonprofit and humanitarian executives, and business leaders in 126 low- and middle-income countries ranked the UN Sustainable Development Goal 14 (“conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development”) as the least important goal. And the ocean received less than 1 percent of all philanthropic funding since 2009 and remains one of the least funded of all the UN Sustainable Development Goals. In addition, as a specific reference to how far $10 billion goes to improve ocean health, one study reported that establishing and maintaining the marine protected areas needed to meet Aichi Target 11 of the Convention for Biological Diversity would cost upward of $10 billion per year.

Consequently, conserving and sustaining our oceans will require significantly more resources.

Governments take the lead on commitments

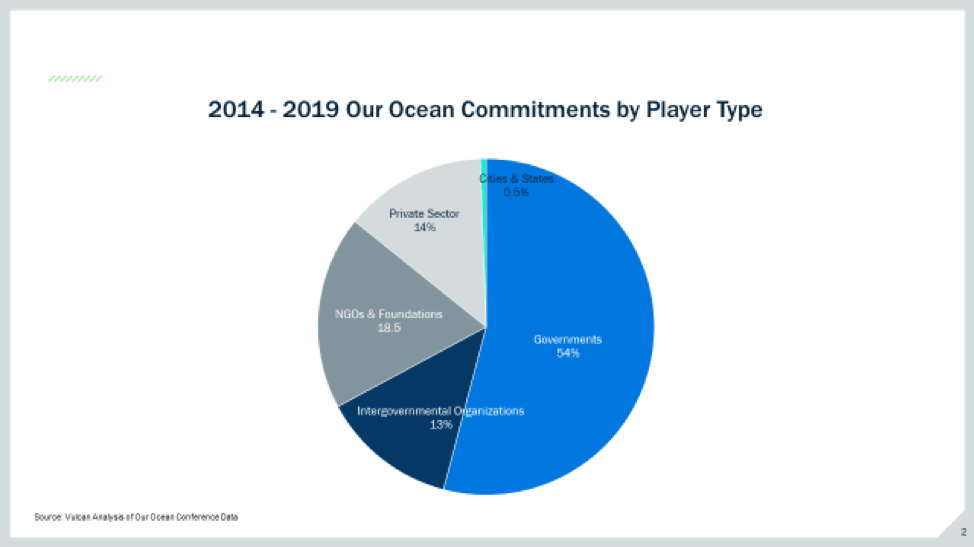

Commitments by national governments and intergovernmental organizations are heavily represented at the Our Ocean conferences. Together, they produced over 65 percent of all commitments made between 2014 and 2019. Considering the plethora of businesses, cities, and states that depend on healthy oceans, it is noteworthy that the latter actors only made 14 percent of the total number of commitments. Moving forward, federal governments are likely to continue to call on the private sector, subnational entities, and the not-for-profit sector to play a larger role in ocean health.

Indeed, this week, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, the Council on Environmental Quality, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration are organizing an event in Washington, D.C. to push for greater collaboration between the public and the private sector on a wide range of ocean issues. Public-private partnership (PPP) is an area where there is plenty of room for improvement for future Our Ocean conferences. In fact, less than 10 percent of all commitments announced at the six Our Ocean conferences feature PPPs.2

The climate-ocean disconnect

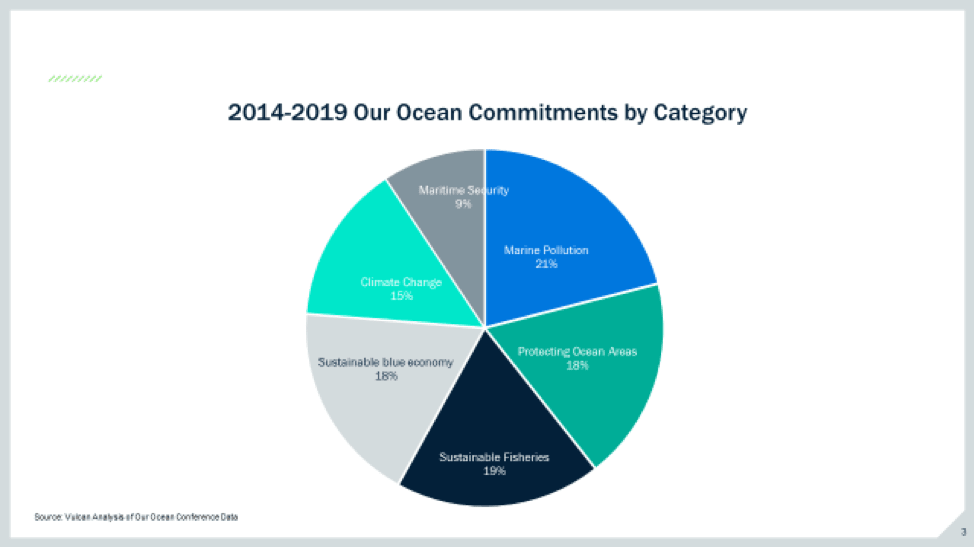

Commitment-makers can elect to position their commitments in one of several ocean health categories: climate change, marine pollution, protecting ocean areas, marine security, sustainable blue economy, and sustainable fisheries.

There is ample evidence of how the climate and oceans can both negatively or positively impact one another. For example, the ocean absorbs approximately 30 percent of anthropogenic CO2 emissions helping to reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Absorbing this CO2, however, causes ocean acidification, which dissolves crustaceans’ shells and threatens coral reefs. More than 90 percent of the excess heat trapped from increased greenhouse gas emissions has passed into the ocean, making hurricanes stronger, causing the sea level to rise, and bleaching corals.

Despite the connection between the climate change and oceans, which most experts believe is the greatest threat to ocean health, climate commitments have only been on par with other commitment categories, as indicated by the below illustration.

However, in 2019, the total number of climate change commitments rose to 21 percent of all commitments, and this 9-percentage point increase is a welcomed development. This positive trend may be a result of recent high-level attention to the ocean-climate nexus. For example, during the UN climate action summit in NYC in September 2019, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a special report on the negative consequences of climate change has on oceans. In addition, the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy recently released an action plan for ocean-based climate solutions. The increased emphasis on the ocean-climate link is important to drive further collaboration between these interconnected communities.

Looking ahead

The government of Palau will host next year’s Our Ocean Conference, and the following year ocean leaders will travel to Panama. These are key opportunities for the ocean community to fine tune their emphasis when making cost-effective and impactful contributions to the health of the seas moving forward.

More organizations should emphasize public-private sector partnerships to leverage financial resources and ocean health tools. The Our Ocean Conference is an exceptional platform to make those partnerships public next year. Why not aim to go from under 10 percent to 50 percent of the commitments being collaborations between public and private, NGOs, foundations, cities, states, and other actors?

Also, with climate change being the greatest threat to ocean health, Our Ocean Conference participants should prioritize climate commitments at future conferences.

And finally, geopolitics and the ocean economy will emerge as a major inflection point in the international system in the coming years and decades. Rising powers will seek to feed their populations by continuing to aggressively go after the ocean’s fish. Competition will also mount over rare earth elements and who will lay claim and secure the enormous wealth that lies on top and beneath the seabed. And current and future trading lanes will be fault lines for great power politics as ice melts in the Arctic as a result of climate change. As the connection between ocean and geopolitics continues to grow, greater emphasis on the geostrategic implications of oceans and its resources should be brought to the Our Ocean Conference series.

Johan Bergenas is senior director for public policy at Vulcan Inc, Rachel Rivera is manager for philanthropic initiatives in the office of the chair at Vulcan Inc, and James Feinstein is a public policy analyst at Vulcan Inc.

-

We reviewed all 1,385 Our Ocean Conference commitments between 2014 to 2019 and categorized them by actor (governments, intergovernmental organizations, NGOs and foundations, private sector, and cities and states) and by theme (climate change, marine pollution, protecting ocean areas, marine security, sustainable blue economy, and sustainable fisheries). For 2019 data, we folded the future Our Ocean conferences commitments into the sustainable blue economy theme. As the Our Ocean Conference themes have evolved over time, we consolidated to maintain consistent themes over the years. For example, the 2014 Our Ocean Conference featured a “preventing and monitoring ocean acidification” theme, which we counted under our “climate change” theme. The 2014 Conference also includes the themes “building capacity,” “supporting coastal communities,” and “mapping and understanding the ocean.” As the commitments in these themes most closely align with the commitments made to the sustainable blue economy theme in subsequent years, we counted them as such. For 2019 data, we rolled the civil society organizations and philanthropist types into the NGOs and foundations type. ↩

-

There is no widely accepted definition of a public-private partnership, but for the purposes of this analysis we used the following methodology: 1) the PPP must involve a government and/or intergovernmental organization in partnership with an NGO, foundation, the private sector, and/or an academic institution; 2) the commitment states that they are entering into a PPP or joint project together; 3) building on previous initiatives or established partnerships are counted; 4) commitments that do not count include: grants, vague references to partners, reaffirming previous commitments (unless expanded upon), and stating support without a quantifiable or explicit contribution. ↩