Illuminating the South China Sea’s Dark Fishing Fleets

Unseen fishing activity. Maritime militias in the Spratlys. Fishers have often been overlooked in the South China Sea disputes. CSIS, in cooperation with Vulcan, Inc., unveils a worrying narrative about the impact fishers and their fleets have in the region.

The South China Sea has emerged as one of the most dangerous flashpoints in the Indo-Pacific over the last decade. With China’s expansion and militarization of its holdings in the disputed Spratly Islands from late 2013, tensions have escalated rapidly.

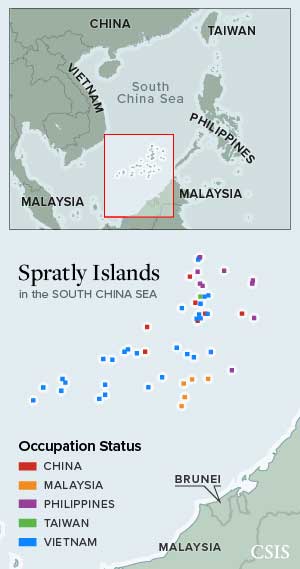

The South China Sea is home to two sets of disputes.

One is over sovereignty. China, Taiwan, Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam claim various islands, rocks, and reefs around the sea.

The other involves those parties and Indonesia. The dispute is over how to divide the sea itself.

Southeast Asian claimants assert rights to overlapping maritime zones under international law.

China and Taiwan, however, claim ill-defined rights over a vast area bordered by the so-called Nine-Dash Line.

The security implications of these disputes receive significant attention, and the disputants’ navies, air forces, and coast guards are studied closely to assess the balance of power and risk of escalation. But too little attention has focused on another key set of actors in the South China Sea—the fishers who serve on the frontlines of this contest. Those fishers face a dire threat to their livelihoods and food security as the South China Sea fisheries teeter on the brink of collapse.

The South China Sea accounted for 12 percent of global fish catch in 2015, and more than half of the fishing vessels in the world are estimated to operate there. Its fisheries officially employ around 3.7 million people and unofficially many more. But the South China Sea has been dangerously overfished. Total stocks have been depleted by 70-95 percent since the 1950s, and catch rates have declined by 66-75 percent over the last 20 years.

Coral reefs, on which much of these fish depend, have been declining by 16 percent per decade. And that decline rapidly accelerated over the last five years in which giant clam harvesting, dredging, and artificial island building have severely damaged or destroyed over 40,000 acres, or about 160 square kilometers, of reefs.

As they race to pull the last fish from the South China Sea, fishers stand at least as much chance of triggering a violent clash as do the region’s armed forces. And that has become even more likely as a significant number of fishing vessels in the area forgo fishing full-time to serve as a direct arm of the state through official maritime militia.

To provide a clearer picture of the size and activities of these important players, CSIS undertook a six-month-long project in cooperation with Vulcan’s Skylight Maritime Initiative to leverage previously underused technologies and data sources to analyze the size and behavior of fishing fleets in the most hotly-contested part of the South China Sea, the Spratly Islands.

The results tell a worrying story about the scale of unseen fishing activity in the region, massive overcapacity in the Spratlys, especially on the Chinese side, and the stunning scale and expense of the maritime militia.

Tracking the Boats

Conducting accurate stock assessments and managing fisheries in the South China Sea is all but impossible because of the overlapping territorial and maritime disputes, which prevent effective enforcement of domestic fishery laws or cooperation among regional states. In fact, some states actively encourage and even subsidize fishing in disputed waters to assert their claims.

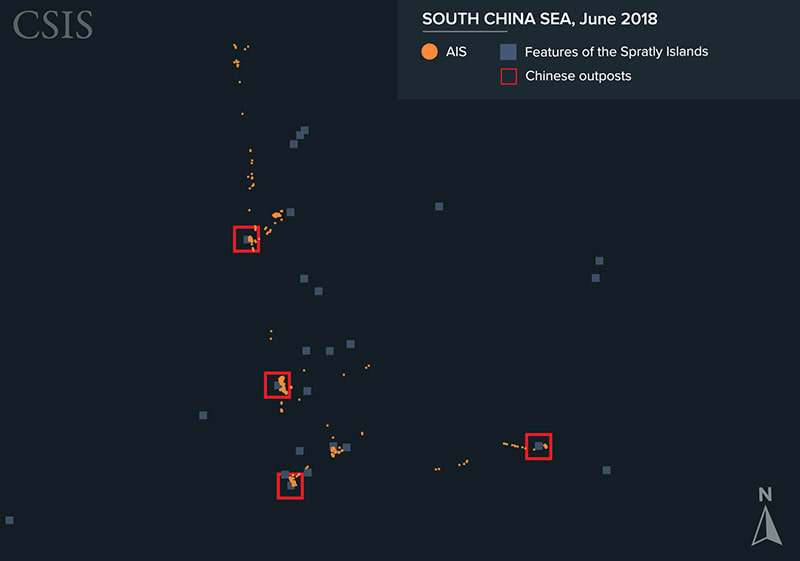

Attempting to monitor fishing activity remotely is uniquely difficult in the South China Sea. But several different technologies—AIS, VIIRS, SAR, and optical satellite imagery—can be combined to monitor this activity.

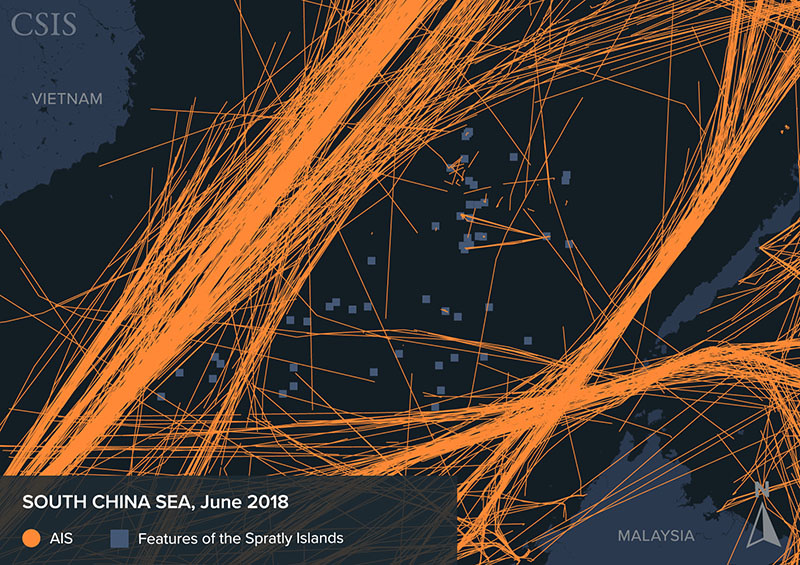

Automatic Identification System (AIS)

For a region where so much fishing is reported, boats are surprisingly difficult to identify in the South China Sea. The Spratly Islands, in particular, are devoid of Automatic Identification System (AIS) signals. The absence of signals is due in large part to the small size and age of many fishing vessels, especially in the Philippines and Vietnam. But many vessels operating in the Spratlys have transceivers and should be using them but choose not to so that they can hide their activities. This necessitates turning to other technologies for a clearer picture of the size and activities of fishing fleets in the South China Sea.

Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS)

One of the most helpful sources of data on fishing in the South China Sea, and around the world, is the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) Boat Detection product, which can detect bright light sources at sea. It reveals a huge amount of fishing activity takes place in the South China Sea, including in and around the Spratly Islands, despite its invisibility in the AIS record.

VIIRS data shows a significant amount of fishing in the South China Sea year-round, with the most active months being March through June. Within the Spratlys, the peak fishing season is March-April. There is also an increase in activity along the coasts of China and Vietnam in August, coinciding with the end of a unilateral three-month fishing ban that Beijing imposes each year in the northern portion of the South China Sea. But most importantly, VIIRS shows that the overall level of activity, regardless of season, has been steadily increasing year to year.

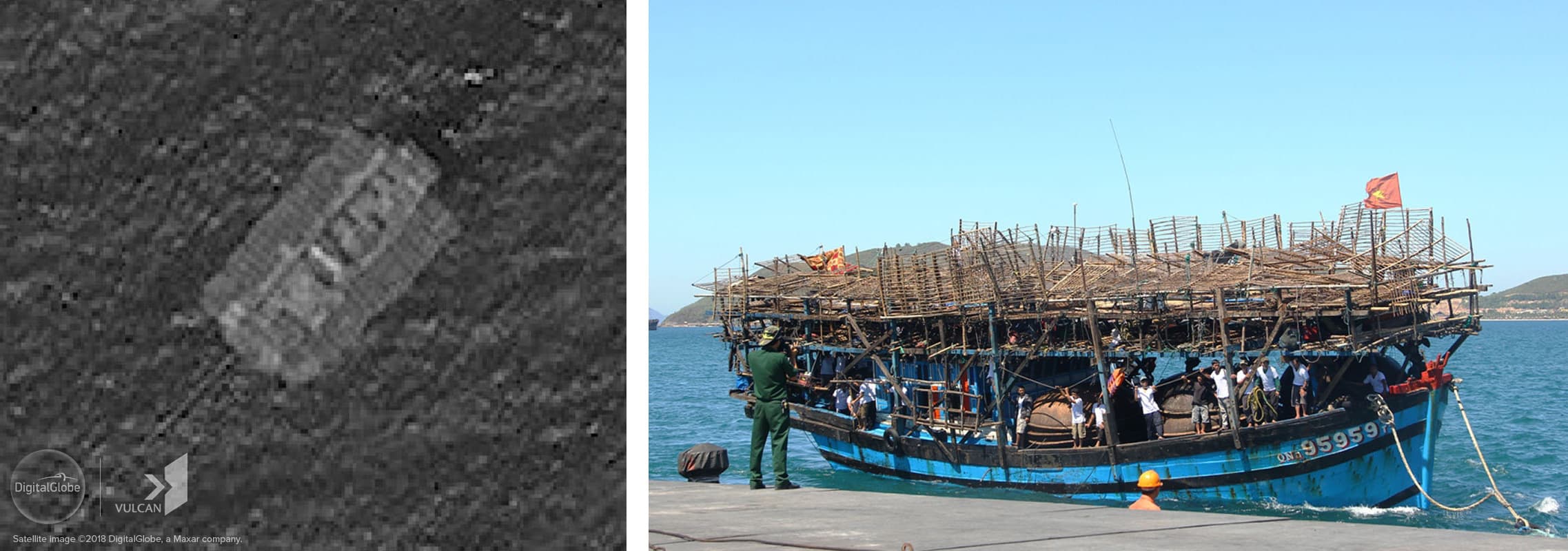

Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR)

For a more granular analysis, Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) provides an approximate count of vessels at a given time and location. Anything metallic, like the hull and superstructure of most modern fishing vessels as small as six meters, can be readily identified by satellite-based SAR. Again, the disconnect between the level of activity and the number of AIS signals being broadcast was staggering. For instance, SAR data collected on eight occasions between September 30 and October 5 provided 264 vessel detections, only 8 of which were broadcasting AIS.

SAR Collections by Area of Interest

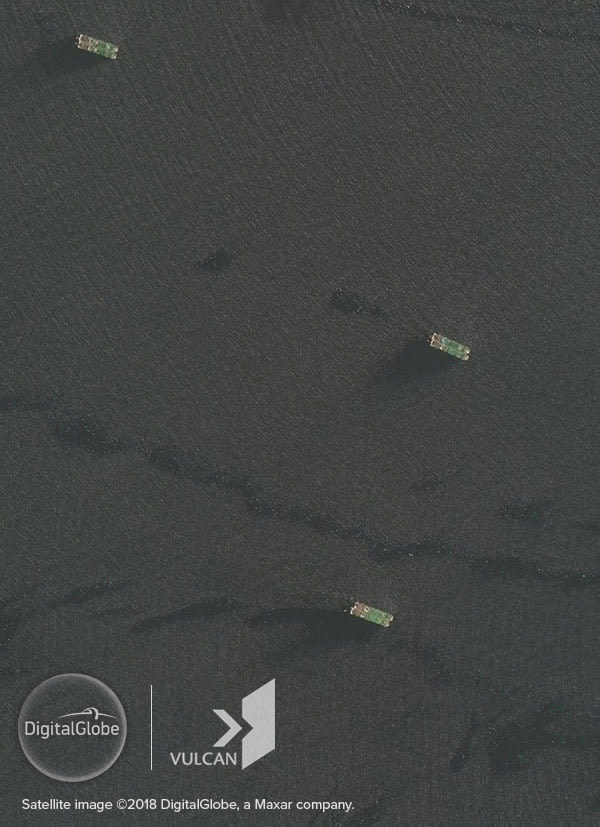

SAR tells much the same story as VIIRS, indicating a significant amount of fishing activity in and around the Spratly Islands. Taken together, they also begin to show the patterns of behavior of fishing vessels in the area. For instance, SAR and VIIRS data suggest that very little activity occurs around those reefs in the southeastern portion of the Spratlys occupied by Malaysia.

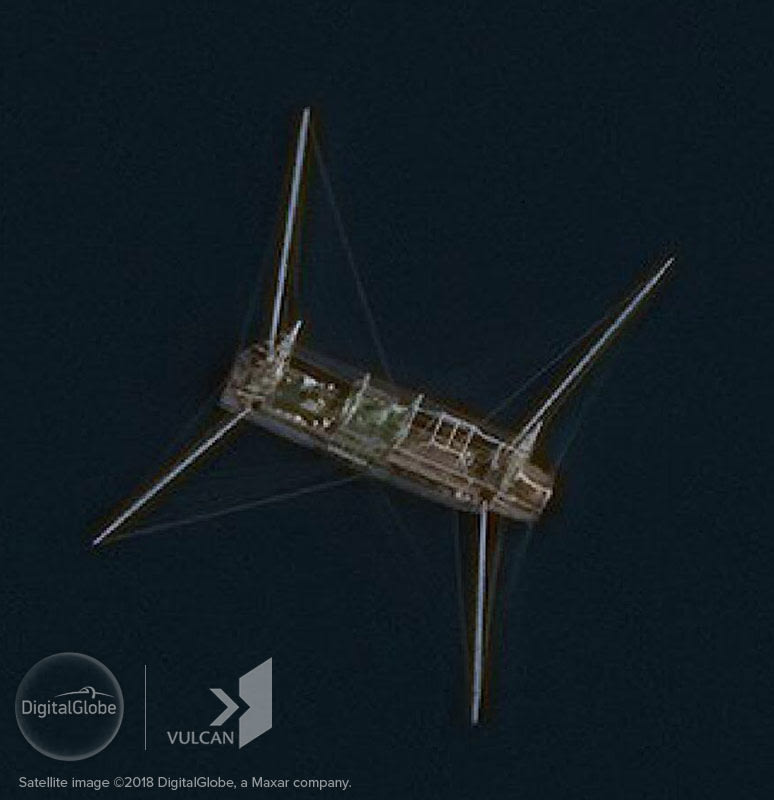

They also show little activity in the unoccupied reefs on the eastern side of the Spratlys, which are near the coast of Palawan in the Philippines. This does not say much about the Filipino fishing fleet that operates in those waters because most of its vessels are small wooden trimarans, called bancas, which would not appear in either VIIRS or SAR. But the absence of returns suggests that other nations’ vessels, which are generally larger and more modern, are not operating around those reefs in large numbers.

On the other hand, SAR and VIIRS indicate a significant amount of activity around the Vietnamese-occupied reefs in the southwest, the central Spratlys where both China and Vietnam have outposts, as well as in the area to the northeast where both Vietnam and the Philippines occupy numerous features.

The biggest story, however, is the massive presence of vessels in and around China’s outposts, particularly its two largest at Subi and Mischief Reefs. Two passes over Subi in August revealed 117 SAR returns within the reef’s lagoon and another 61 in waters nearby, including around Philippine-occupied Thitu Island just over 12 nautical miles away. Two passes in October showed an even larger but more dispersed number of returns, with 19 in the lagoon and 190 in waters nearby.

Fishers and Those Not Fishing

While SAR can provide an estimate of fleet size, it cannot reveal much detail about individual ships. For that, the best tool in the absence of AIS is high-resolution satellite imagery, which provides important context. This imagery shows that Chinese fishing ships account for the largest number of vessels operating in the Spratlys by far.

Just as SAR suggests, most of these congregate in the lagoons at Subi and Mischief Reefs, and in nearby waters including around the Philippine-held islets close by. In fact, imagery shows that the numbers of fishing vessels at Subi and Mischief Reefs are even higher than SAR would suggest because they often tie up side by side in large groups, which appear to be a single vessel in SAR.

An analysis of historical imagery shows that the numbers of Chinese ships at Subi and Mischief were much higher in 2018 than in 2017. In August, which appears to have been the busiest month, there were about 300 ships anchored at the two reefs at any given time. Over 90 percent of these were fishing vessels with an average length of 51 meters and a projected displacement of about 550 tons.

In almost every case, the Chinese fishing boats captured in imagery are riding at anchor or transiting without fishing. Occasionally, imagery revealed a falling net vessel, a common type of Chinese ship observed, engaged in fishing, but such instances were rare.

In addition to the fleets at Subi and Mischief, clusters of around 10 large Chinese fishing vessels were seen gathered around Philippine-occupied Thitu and Loaita Islands and Taiwan-occupied Itu Aba Island. These clusters remained for weeks at a time and only a few vessels showed signs of fishing during the time period imagery was collected. Overall, the Chinese fleet in the Spratlys spends far less time fishing and far more time at anchor than is typical of vessels elsewhere.

Not only does imagery analysis show that most Chinese fishing vessels in the Spratlys are not fishing very often but that they could not do so sustainably. The size and quantity of Chinese vessels observed in the Spratlys suggests a massive overcapacity.

Based on published Chinese catch levels, a 550-ton light falling net fishing vessel could catch about 12 metric tons per day. That means the more than 270 fishing boats present at Subi and Mischief Reefs in August could catch about 3,240 metric tons per day or nearly 1.2 million metric tons per year. That is between 50 and 100 percent of the total estimated catch in the Spratly Islands.

This gross overcapacity combined with their tendency to congregate around both Chinese-occupied reefs and those held by other claimants leads to the conclusion that most of these vessels serve, at least part-time, in China’s maritime militia.

The activities of the militia are well-documented—they engage in patrol, surveillance, resupply, and other missions to bolster China’s presence in contested waters in the South and East China Seas. Beijing makes no secret of their existence, and some of the best-trained and best-equipped members engage in overt paramilitary activities such as the harassment of foreign vessels operating near Chinese-held islets or dangerous standoffs with vessels from neighboring states as occurred in 2014 when China deployed an oil rig in waters claimed by Vietnam. But this analysis indicates that their numbers in the Spratly Islands are much larger and much more persistent than is generally understood.

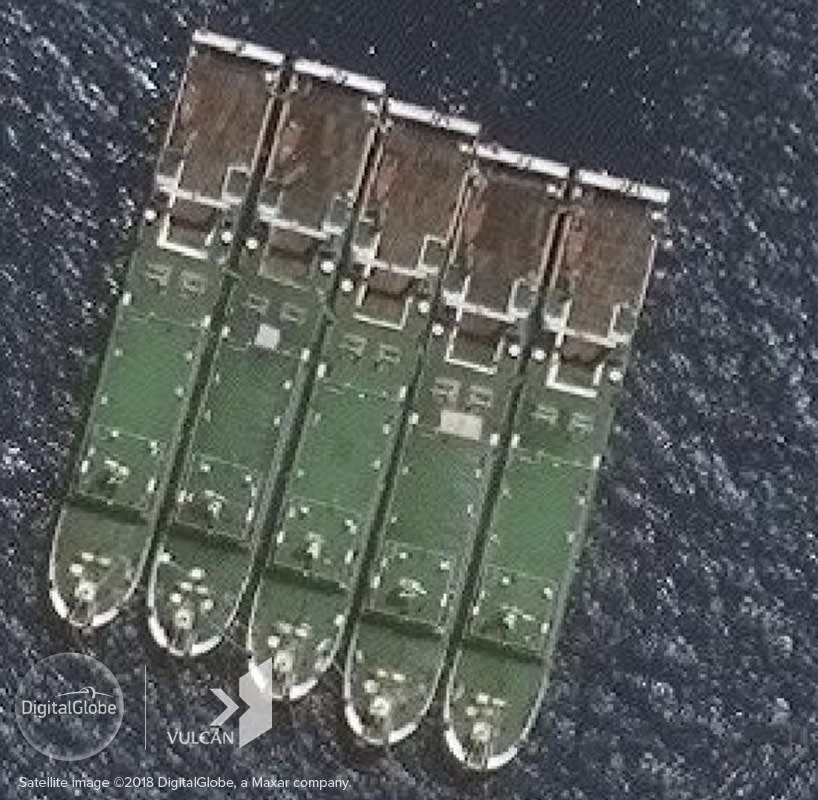

The Yue Tai Yu Fleet

The story of one set of these militia ships, the Yue Tai Yu fleet, is instructive and highlights just how much Beijing has invested in the militia in recent years.

The nine vessels named Yue Tai Yu 18000 through 18999 are each 62.8-meter trawlers. They were built by Guangxin Shipbuilding & Heavy Industry in 2017.

Like most Chinese fishing ships in the South China Sea, they rarely transmit AIS data, despite being legally required to do so. But they have transmitted enough to determine that they left Guangxin, traveled to the coastal port of Shadi, and spent the intervening year traveling back and forth between this homeport and the Spratly Islands.

The vessels have made lengthy stays at Subi and Mischief Reefs and visited China’s facilities at Gaven, Johnson, and Hughes Reefs. But their maritime militia status seems apparent from time spent loitering in the waters around Philippine-occupied Thitu and Loaita Islands.

The Yue Tai Yu vessels have been captured in satellite imagery on several occasions, and neither these images nor the patterns seen in their intermittent AIS transmissions show that the ships spend much, if any, time fishing. That means these large modern trawlers, which likely cost $100 million or more to build, are not producing much commercial benefit to their owners. If they are any indication, Beijing is sinking a stunning amount of money into subsidizing the operations of a massive and largely unproductive fishing fleet in the Spratly Islands.

Conclusion

The fisheries and fishers of the South China Sea warrant much more attention. The disputes over the islands, reefs, and waters in the area have made effective fisheries management impossible even as a calamitous stock collapse threatens livelihoods around the region. Tools like VIIRS and SAR show that the number of fishing vessels operating in the disputed Spratly Islands is exponentially higher than AIS transmissions suggest. Improving the monitoring of these fleets will be critical if the claimants hope to save the South China Sea fisheries and reduce the frequency of unlooked-for incidents between vessels.

Meanwhile, a different kind of fishing fleet, one engaged in paramilitary work on behalf of the state rather than the commercial enterprise of fishing, has emerged as the largest force in the Spratlys. The numbers of militia vessels operating in the area on behalf of China is much larger and more persistent than is generally understood. Experts and policymakers focused on the South China Sea will need to devote a proportionate amount of their attention to these actors and the role they play in the area.